On a fateful morning in 1908, a deafening explosion shook the Tunguska region of Siberia. Trees were leveled across 2,000 square kilometers, the sky lit up with an eerie glow, and seismic stations worldwide recorded the event. Yet, there was no crater to be found. Was it an asteroid? A comet? Or could it have been something far more exotic—a black hole?

Hold on to your seats as we delve into the cosmic nightmare of black holes hitting Earth. Could it happen? Has it already happened? Let’s explore the chilling possibilities, the science, and—thankfully—the odds.

Black Holes: The Universe’s Cosmic Creepers

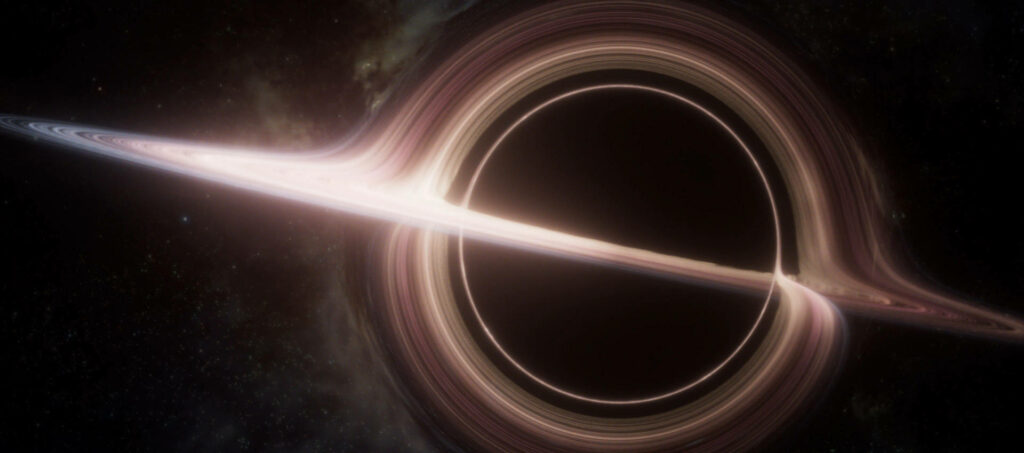

Black holes are equal parts fascinating and terrifying. They are gravitational monsters that can bend light, tear apart stars, and stretch unlucky matter into spaghetti. But could one actually hit Earth?

The good news: supermassive black holes—the ones millions of times the mass of the Sun—are too far away to pose a threat. They lurk at the centers of galaxies, including our own Milky Way. If one were nearby, we’d definitely notice its gravitational mayhem.

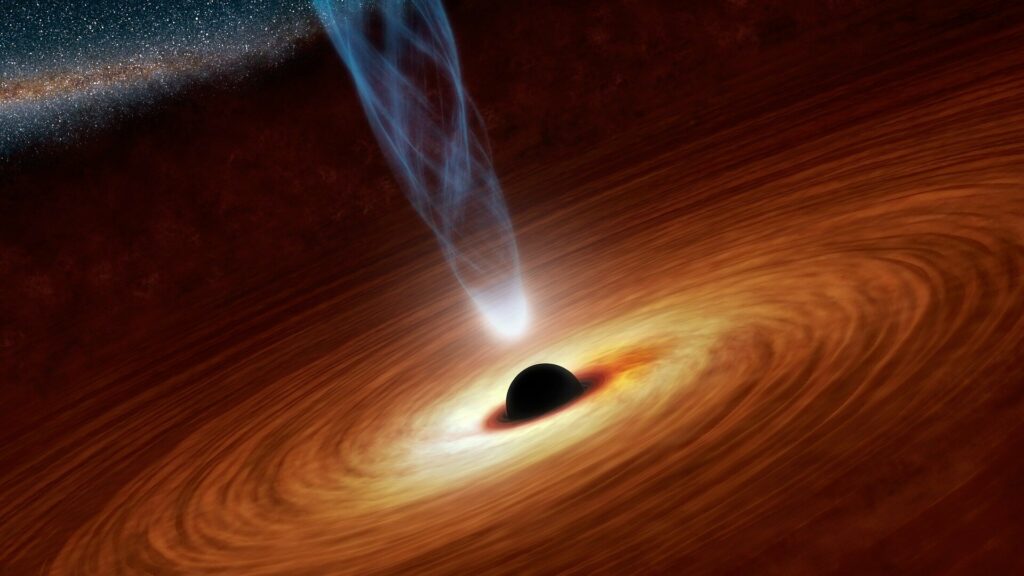

The bad news: stellar black holes—formed from the collapse of massive stars—are much stealthier. Unless they’re actively consuming matter, they’re invisible to the naked eye. Astronomers can detect them if they’re part of a binary system (feeding off a companion star), if they warp background light through gravitational lensing, or if they merge with other compact objects and emit gravitational waves.

But what about rogue black holes? Stellar black holes are thought to roam the galaxy in vast numbers—an estimated 100 million in the Milky Way alone. Statistically, there might be one as close as 40 to 80 light-years from Earth. And since these objects are often ejected at high speeds during their formation in supernova explosions, they’re zipping around unpredictably.

A Black Hole in the Neighborhood: Scenarios and Survival

What if a black hole wandered into our solar system? The effects would depend on its mass, trajectory, and proximity. Let’s consider three possible scenarios:

Scenario 1: A Close Pass

If a black hole passed near the outer planets, like Jupiter or Saturn, it wouldn’t be pretty. Its immense gravity could destabilize planetary orbits, potentially flinging Earth out of the solar system or into the Sun. Rogue asteroids might also be nudged into collision courses with Earth. This cosmic billiards game would wreak havoc, but the odds of this happening are relatively low—around 0.01% over Earth’s 4.5-billion-year history.

Scenario 2: A Gravitational Tug-of-War

If a black hole came close to Earth without directly hitting it, the results would still be catastrophic. Gravitational forces would cause extreme tidal stresses, heating Earth’s core and triggering massive earthquakes, tsunamis, and volcanic eruptions. Life as we know it would likely be wiped out. Thankfully, this scenario is also quite rare, with odds of about 1 in 10 million.

Scenario 3: The Direct Hit

This is the nightmare fuel: Earth falls directly into a black hole. The result? Spaghettification. Earth would be stretched and torn apart by the black hole’s immense gravity. The atmosphere would be stripped away, and the remaining material would form a glowing accretion disk before being consumed entirely. The whole process would take mere seconds. Fortunately, this apocalyptic scenario is vanishingly unlikely, with odds of just 1 in 100 billion over Earth’s lifetime.

Could Humans Create a Black Hole?

Could we inadvertently summon doom through our own scientific curiosity? Enter the Large Hadron Collider (LHC), the world’s most powerful particle accelerator. While some have speculated that high-energy collisions at CERN could create microscopic black holes, the answer is a resounding no.

Even the most energetic collisions in the LHC are billions of times weaker than the natural cosmic accelerators found in the universe, like supernovae or gamma-ray bursts. If microscopic black holes were possible, we’d already see evidence of them in nature—and we don’t.

The Mystery of Primordial Black Holes

While human-made black holes are out of the question, there’s another possibility: primordial black holes. These theoretical black holes might have formed in the early universe, with masses ranging from a grain of sand to an asteroid. Could they still be around, and might one have caused the Tunguska event?

The Tunguska Mystery Revisited

The 1908 Tunguska explosion flattened Siberian forests but left no crater, puzzling scientists for decades. Most believe it was caused by an asteroid or comet that exploded mid-air, but what if it was a primordial black hole?

Here’s how it would have looked:

- Atmospheric Entry: The black hole would generate intense heat, creating a brilliant light streak like a massive meteor.

- Earth Piercing: It would pass through the Earth in about a minute, consuming only a few thousand tons of material—a negligible amount on a planetary scale.

- Shockwaves: Its path would create powerful seismic and atmospheric shockwaves, similar to those observed at Tunguska.

The problem? A black hole exiting the Earth should produce a secondary shockwave on the opposite side, but no such evidence exists. It’s still more likely that Tunguska was caused by an airburst from a comet or asteroid.

Looking for Evidence: The Moon as a Witness

If primordial black holes have struck celestial bodies, the Moon is the ideal place to look. Unlike Earth, it has no atmosphere or plate tectonics to erase impact evidence. A black hole would create distinctive craters—small, deep, and paired with an exit crater linked by a subsurface tunnel.

To date, no such craters have been found, but if we ever do discover them, it would be a groundbreaking confirmation of primordial black holes.

Should We Be Worried?

The universe is a chaotic and sometimes terrifying place, but the odds are on our side. The fact that Earth still exists after billions of years is proof that catastrophic encounters with black holes are exceedingly rare.

So, while black holes remain fascinating cosmic enigmas, you can rest easy. The sky may hold its mysteries, but for now, it’s more friend than foe.